What is a nation without its history, its culture, its shared memories? This idea strongly resonates in Italy. Italy is a country where culture and history starkly shapes identity, present realities and future opportunities. That’s why it has always committed to protect heritage around the world – whether archeological sites, historical artefacts or intangible cultural assets. And that’s what we also believe.

Since Russia’s full‑scale invasion in February 2022, Ukraine has not only fought for its land but also for its memory. Cultural sites have been bombed, libraries burned, and museums looted. As of 16 April 2025, UNESCO has verified damage to 485 sites since the full‑scale invasion, including 149 religious sites, 257 buildings of historical and/or artistic interest, 34 museums, 33 monuments, 18 libraries, 1 archive and 2 archaeological sites. “It is a war against our memory, against our identity and culture, and of course against our future,” says Ihor Poshyvailo, director of the Maidan Museum in Kyiv.

Modest revolution

Driven by these beliefs that a nation should always know where it comes from – whether in war or peace — a new mobile safeguard unit has embarked on its historic first mission in the heart of Kyiv.

Modest in appearance but revolutionary in function, it is part of the Ark for Ukraine project—an initiative that combines cutting‑edge technology with cultural solidarity. Developed by the Karel Komárek Family Foundation (KKFF) in partnership with the Czech and Ukrainian Ministries of Culture, the Czech National Library, and the National Museum, the Ark project is a mobile effort to digitally preserve Ukraine’s endangered cultural treasures before they disappear forever.

The project’s origins connect to the Czech Republic’s own painful history. Devastating floods in the late 1990s and early 2000s destroyed countless cultural materials, prompting a national campaign to digitize archives and safeguard them against future loss. That hard‑earned expertise is now being applied in Ukraine.

„We knew how to respond because we had experienced disasters affecting cultural heritage.“

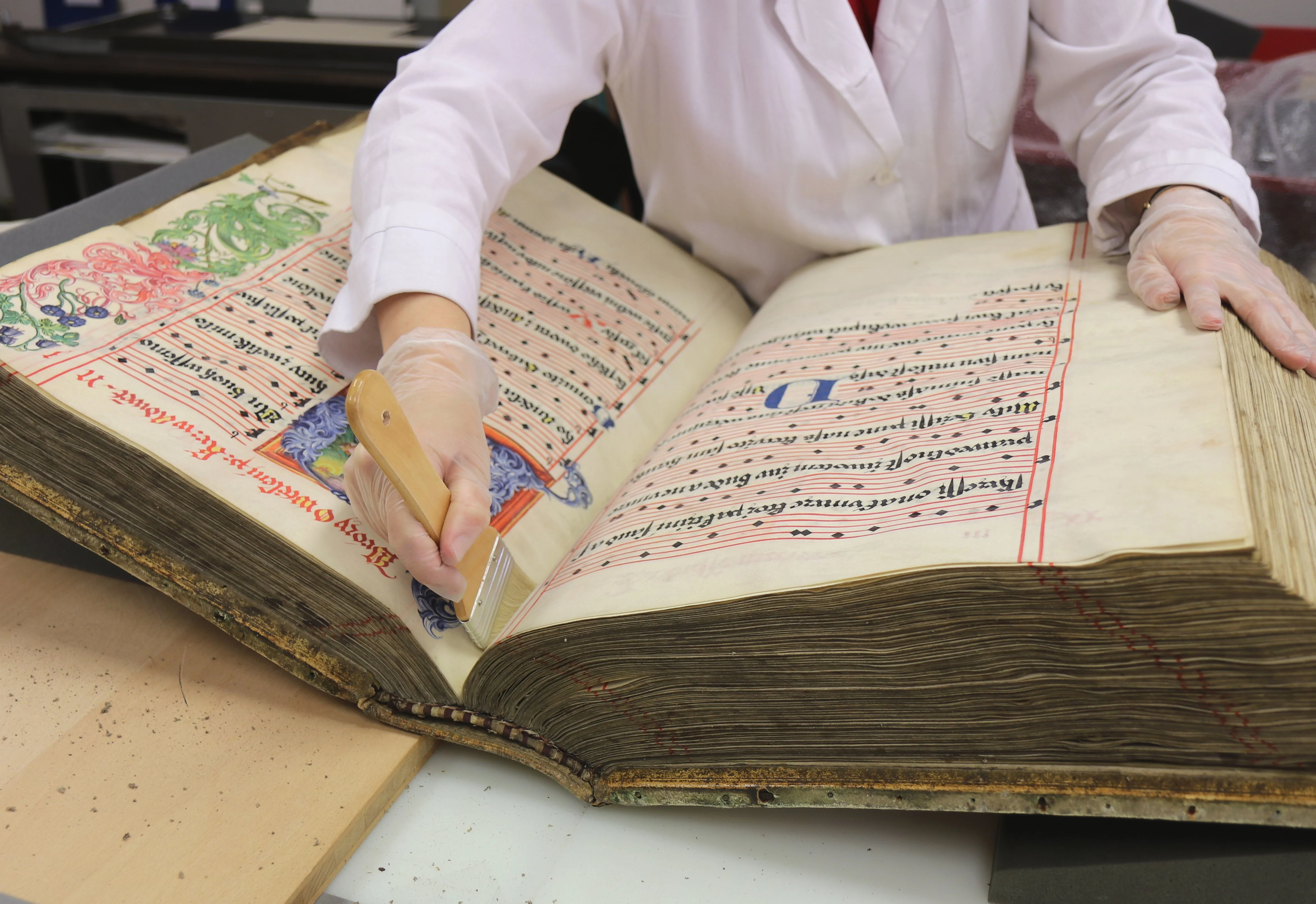

Ark’s mobile units operate like field hospitals for culture. The first vehicle, Ark I, is equipped with special tools for urgent and immediate interventions and on‑site repairs of library collections, including a portable stock of necessary materials. It’s been deployed to partner institutions across Ukraine, supporting local professionals under siege.

One of those professionals is Oleh Serbin, Director of the Yaroslav Mudryi National Library of Ukraine.

„We conduct trainings, education, so that our colleagues go to the regions and scale this knowledge, and are prepared to receive this station, so that upon arrival there it immedi‑ately starts working.“

Now, with the launch of Ark III, the initiative has moved into even more ambitious territory: 3D scanning of museum artifacts. Housed in a compact van, Ark III is going to travel to threatened museums, capturing the form and detail of sculptures, ceremonial objects, and folk art using advanced 3D imaging. These digital models can be archived, studied, and one day—if necessary—used to recreate what has been lost.

Race against time

“This is a race against time,” says Maksym Ostapenko from the National Preserve Kyiv‑Pechersk Lavra: “We’ve already hidden some artifacts in basements. But if the building is hit, they could be crushed. With Ark, we know their stories can survive.”

The impact is more than technical. The presence of Ark teams—often with Czech and Ukrainian experts working side by side—sends a powerful message. “It shows we’re not alone,” says Ostapenko.

„Someone far away understands that our culture matters.“

That understanding is spreading. At cultural forums, European leaders have echoed the urgency. Oleksandra Matviichuk, Human Rights Lawyer, addressed guests at a fundraiser in London in February 2025, “Putin openly says there is no Ukrainian nation, there is no Ukrainian language, there is no Ukrainian culture. For 11 years, we have been documenting how these words converted into horrible practice.”

The international community is beginning to act. UNESCO has designated enhanced protection to 20 Ukrainian cultural sites. The UK has called the destruction of cultural heritage a war crime. But the work on the ground—quiet, technical, and relentless—is being led by Ukrainians themselves, supported by Ark’s mobile lifelines.

Public‑Private Partnership

Donations from private citizens and philanthropic organizations are helping expand Ark’s reach. Plans include additional vehicles, training for Ukrainian cultural workers, and the establishment of secure digital archives. Each contribution supports not just equipment, but the people using it to rescue their past.

The Karel Komárek Family Foundation has already secured 50 % of the funding needed to sustain and expand the ARK project. Now, it calls on individuals, institutions, and partners across the world to help complete the mission.

„The reason we are part of this project is that we grew up in Czechoslovakia, which was under the influence of the Soviet Union for some time. We all remember very well what freedom means. Freedom of expression and culture are extremely important for every nation, because without culture, a country is just a territory – without a past and without a future.“

In a conflict defined by loss, the Ark project offers something rare: a means of preservation, and even restoration. It captures images and data, and preserves dignity. In doing so, it ensures that Ukraine’s story will not be silenced.

Because if Ukraine’s history is lost, it’s not only Ukraine that suffers. The story of Europe — and indeed, our shared human story — becomes incomplete.

As director Poshyvailo puts it, “They can try to destroy our monuments. But as long as we remember—and as long as we preserve what we can—they will never destroy our memory.”

Newsletter